Human-centred invention

Why augmented reality is garbage, and how to make it transcendent and good and funny, OR a lesson in wielding the magic of socio-technical ergonomics.

Why augmented reality is garbage, and how to make it transcendent and good and funny, OR a lesson in wielding the magic of socio-technical ergonomics

Once again we are on the cusp of a new world; the only big tech company that gives a damn about human-centred design will soon bring their next revolutionary device to market. Yes, that’s Apple; and yes, it’s their forthcoming augmented reality headset.

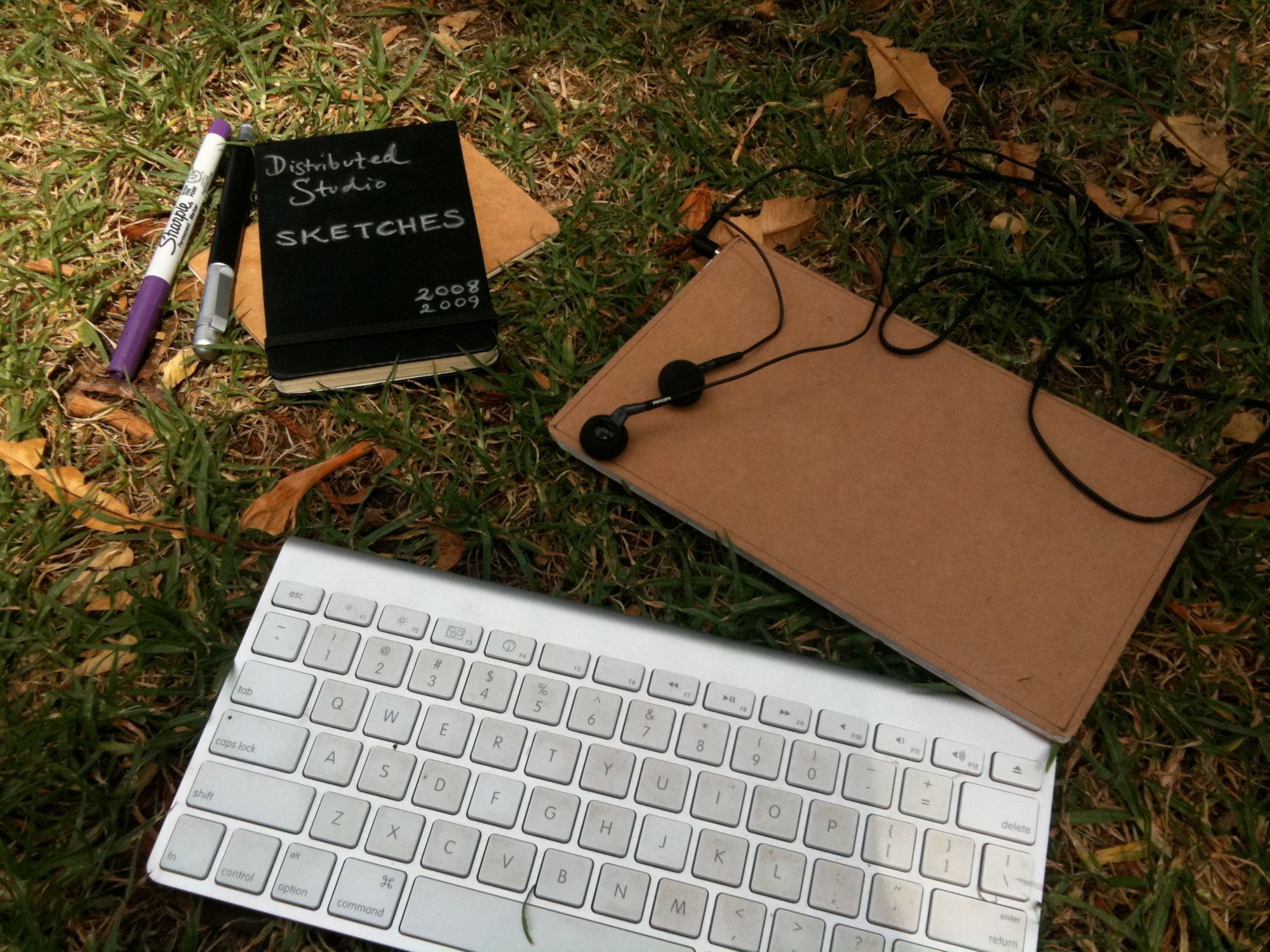

I’ve been here before, writing on this side of the reality shear; in the lead-up to the original iPad reveal, when every tablet computer was still garbage, I had spent several months in phenomenological enquiry. That means I had unaccountably been walking around with weighted mockups of various form factors for imaginary tablets in my pockets and satchels, to feel their heft and discover the affordances and constraints they would reveal; to sense the range of possibilities before it was too late.

Because as I predicted at the time, at the moment of the iPad release the probability waveforms collapsed. We are now in a world where it’s nearly impossible to imagine tablet computing working any other way. Every competitor now apes the iPad, presenting a grid of icons in a magazine-sized glass rectangle with capacitive touch interaction. The only substantial improvement has been Apple’s own introduction of a stylus. Microsoft’s innovative Duo book concept impacted on the surface and was never seen again. Maybe one day someone will make a good folding one.

The situation today is similar: none of the augmented reality devices so far have been good enough, because no-one is being serious about human-centred design.

That wasn’t always true – many of the smaller experiments, born too early to survive, had incredible promise. Daqri with their smart helmets for construction sites; Steve Mann’s deeply considered longitudinal experiments in cybernetic augmentation; the many beautiful thoughtful bespoke systems that pop up at the conference on Tangible and Embedded Interaction or in a demo by some curious Japanese research lab at SIGGRAPH Emerging Technologies.

It is however sadly true of the big, well funded projects we’re seeing today. The Microsoft Hololens is technically impressive but unfocused – who is it meant to be for? Do you expect me to run Office apps on this thing? Why does Bing keep throwing a huge 2D browser window up at me? Do you people really think I should have to poke my corporate password into a floating keyboard before you’ll let me display an object? And where's the support for shared views? I want this to work so badly, but that's exactly how it does work.

The other great hope – Magicleap – figured they could get there with a commitment to beauty and learning, which would have worked if we lived in a just world.

But no, this is harder than that. You need to get the design right, but you also need to have chosen the right design. And just like last time, it’s all about the form factor.

The form factor is how the object presents itself to the user; how it fits their body and their life. It’s the size, weight, texture, behaviour under different conditions of light and noise and atmosphere. Fit and finish.

Until Bas Ording demonstrated the interaction potential of capacitive touch to Steve Jobs there could be no iPhone. And as the device went into development his collaborator Imran Chaudhri (now co-founder of the mysterious and compelling hu.ma.ne) maintained a relentless insistence that this aspect of the experience could not be compromised. As Ken Kocienda relates in the masterful Creative Selection, he would place a sheet of paper on a glass table and push it around with his finger. Like this! No perceptible delay, no break in the illusion of direct manipulation, not for anything.

The size and shape of the device was no less important. A deck of cards could have any form factor, but it’s a 4-inch diagonal rounded rectangle, because that’s what works for humans. The iPhone, like the iPod, is a deck of cards. The iPad is a sheet of paper.

What the hell is this?

Humans have chosen the form factors for things to put on our heads. Hats. We like hats. Helmets. Headbands and earmuffs and headphones. Goggles if necessary. Spectacles, if they’re light enough.

One thing we have never chosen is a vice. We don’t enjoy putting our head in a clamp and screwing it tight. Now, I can tell that what they think they’re going for here is spectacles. Because that’s what people look through, right?

No. Stop it. You’re doing this wrong.

We do not have the technology to make something lightweight enough to be acceptable as spectacles. The Hololens is over 500g. Let’s say Apple can engineer that right down to a quarter of the weight: 125g. Still no.

So – are there items between 125g and 250g that people are willing to wear on their heads?

Next, let’s talk about fashion.

Google Glass was launched with a fashion-forward strategy. It all seems like a fever dream now but I seem to remember Sergei Brin parachuting onto a stage at Fashion Week with a bevy of models all bedecked in cybernetic headsets. Because I guess that’s how the kids at Google reckon fashion works. Famous beautiful people wear things at high profile events, and everyone follows along, right?

Well. You think you know fashion, but fashion’s a stranger. You think fashion’s your friend; my friend – fashion is danger.

Everything I know about fashion I learned from Flight of the Conchords, so that’s not much. But I know a little about cultural creativity. The famous high-profile people usher it onto the stage, but they don’t make it happen. Fashion, like all creativity, emerges from a cultural milieu. Coco Chanel was working in a Paris where women who wanted to challenge gender and sexuality were already retailoring men’s uniforms for themselves. Her brand caught on because the moment was right.

Now to the magic spell. The simple incantation that can only be cast by those who are willing to grapple with the eldritch relationship between ergonomics, form factor and the Rogers Curve that describes the Diffusion of Innovation.

There are some known routes for a new kind of clothing to get into the mainstream. For example: street wear, dance wear, sportswear.

Of these, the most overwhelmingly correct path from a niche into the mainstream for augmented reality is sportswear.

People will wear all kinds of things in a sports or fitness context. Padding, lycra, helmets, visors, even fins. Fitness is virtuous and pragmatic; these things lower the threshold of acceptability. And then once people get used to it, the new form makes its way into everyday clothing.

Running changed shoes. Yoga changed pants. Augmented reality fitness is going to change the hat.

/eof